Word versus Markdown: more than mere semantics

Our default content publishing workflow is terribly broken. We’ve all been trained to make paper, yet today, content authored once is more commonly consumed in multiple formats, and rarely, if ever, does it embody physical form. Put another way, our go-to content authoring workflow remains relatively unchanged since it was conceived in the early ’80s.

I’m asked regularly by government employees — knowledge workers who fire up a desktop word processor as the first step to any project — for an automated pipeline to convert Microsoft Word documents to Markdown, the lingua franca of the internet, but as my recent foray into building just such a converter proves, it’s not that simple.

Markdown isn’t just an alternative format. Markdown forces you to write for the web.

In the beginning, there was paper

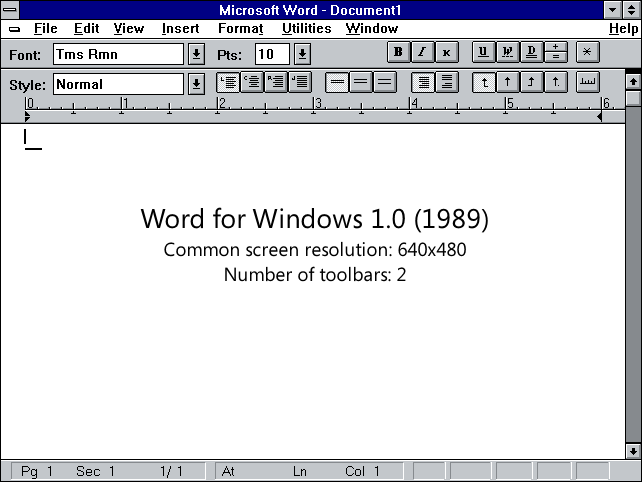

The first desktop word processors had a simple task: they were designed to make paper. We didn’t have email or a vibrant internet sharing digital documents to worry about. The creators of the first desktop word processors simply mirrored the dominant workflow of the time: the typewriter. The final output — the sole embodiment — was physical, and all that mattered was what the document looked like.

Over the past three decades, however, how we consume content has changed dramatically, yet, how we author content remains relatively unchanged. Put another way, the internet is a fundamentally different animal than the desktop. You can’t simply take a desktop format and put it online, and “converting” a document to Markdown doesn’t do much to solve that.

Separating content from presentation

Desktop formats are a shallow format — all they care about are looks. Desktop publishing software inextricably marries content and presentation. The information you input can only be consumed in one form, and that one form is defined by the medium, in most cases, paper, or more recently, their digital analog, faux margins and all.

When you blindly optimize for one thing — appearances — behind the scenes there’s a lot that goes unattended and it becomes increasingly complex to perform even the most simple of tasks. Extracting your content becomes tantamount to finding a needle in a purpose-built, legacy haystack.

Put another way, in taking a look at this sample Word Document, given the same content represented identically in various formats, as little as less than one quarter of one percent of the file is actually dedicated to storing content:

| Format | Size | % |

|---|---|---|

| Word | 33621 bytes | 100% |

| HTML | 1359 bytes | 4.04% |

| Markdown | 80 bytes | 0.24% |

Exposing author intent

Once content and presentation are decoupled, content written for the web exposes author intent through semantic markup — markup which describes the relationship between elements, not simply their visual representation. It’s not simply that a given line is bold or a larger font size, but memorialized in the document itself is that the given line is a heading, a heading which describes the content that follows.

Take a look at how Markdown represents an unordered list, for example:

* One

* Two

* Three

Simplicity aside, the markup represents a grouping with three elements. We, as humans, can tell that those are three parts of a set, and a computer can as well. Now here’s how Microsoft Word conveys the same exact information, at least when exported as HTML:

<p class=MsoListParagraphCxSpFirst style='text-indent:-.25in;mso-list:l0 level1 lfo1'><![if !supportLists]><span

style='font-family:Symbol;mso-fareast-font-family:Symbol;mso-bidi-font-family:

Symbol'><span style='mso-list:Ignore'>�<span style='font:7.0pt "Times New Roman"'>

</span></span></span><![endif]>One</p>

<p class=MsoListParagraphCxSpMiddle style='text-indent:-.25in;mso-list:l0 level1 lfo1'><![if !supportLists]><span

style='font-family:Symbol;mso-fareast-font-family:Symbol;mso-bidi-font-family:

Symbol'><span style='mso-list:Ignore'>�<span style='font:7.0pt "Times New Roman"'>

</span></span></span><![endif]>Two</p>

<p class=MsoListParagraphCxSpLast style='text-indent:-.25in;mso-list:l0 level1 lfo1'><![if !supportLists]><span

style='font-family:Symbol;mso-fareast-font-family:Symbol;mso-bidi-font-family:

Symbol'><span style='mso-list:Ignore'>�<span style='font:7.0pt "Times New Roman"'>

</span></span></span><![endif]>Three</p>

There’s two things you’ll notice there. First, the markup isn’t semantic, meaning the presentation information is intermingled with the content, rendering the author’s intent indiscernible and using the content in any other context an increasingly difficult goal.

Second, there’s a lot of proprietary metadata in there (everything that’s orange or red), useful only for parsing within Microsoft Word. Again, rendering the content as alien anywhere other than its original context, paper.

Jailbreaking content

There’s a reason that content authored on the desktop is most commonly shared online as a PDF — a format designed to mimic the properties of paper as closely as possible. Once the content’s in a paper-based format, it’s stuck there forever.

If there’s one thing I’ve learned trying to convert Word documents to Markdown, it’s that Markdown is not an alternative to traditional desktop formats. It’s an entirely different animal. It’s both machine- and human-readable, but more importantly, it forces you to author content openly, semantically, and for an internet-based world.

Next time you begin a new project for which the internet, not paper is the primary output, think twice before firing up that desktop publishing platform. You’ll gain more than mere semantics.

If you enjoyed this post, you might also enjoy:

- Four characteristics of modern collaboration tools

- 15 rules for communicating at GitHub

- Why open source

- Why everything should have a URL

- Twelve tips for growing communities around your open source project

- Five best practices in open source: external engagement

- 19 reasons why technologists don't want to work at your government agency

- We've been trained to make paper

- How I re-over-engineered my home network for privacy and security

- Speak like a human: 12 ways tech companies can write less-corporate blog posts

- If you liked it then you should have put a URL on it

Ben Balter is the Director of Hubber Enablement within the Office of the COO at GitHub, the world’s largest software development platform, ensuring all Hubbers can do their best (remote) work. Previously, he served as the Director of Technical Business Operations, and as Chief of Staff for Security, he managed the office of the Chief Security Officer, improving overall business effectiveness of the Security organization through portfolio management, strategy, planning, culture, and values. As a Staff Technical Program manager for Enterprise and Compliance, Ben managed GitHub’s on-premises and SaaS enterprise offerings, and as the Senior Product Manager overseeing the platform’s Trust and Safety efforts, Ben shipped more than 500 features in support of community management, privacy, compliance, content moderation, product security, platform health, and open source workflows to ensure the GitHub community and platform remained safe, secure, and welcoming for all software developers. Before joining GitHub’s Product team, Ben served as GitHub’s Government Evangelist, leading the efforts to encourage more than 2,000 government organizations across 75 countries to adopt open source philosophies for code, data, and policy development. More about the author →

This page is open source. Please help improve it.

Edit