Towards a More Agile Government

The Case for Rebooting Federal IT Procurement

41 Pub. Cont. L.J. 149, The Public Contract Law Journal, Fall 2011

- Table of Contents {:toc}

Like many government computer systems, the U.S. federal information technology (IT) procurement model is slow, outdated, and long overdue for a reboot.1 As the largest single purchaser of code, 2 in fiscal year (FY) 2010 the Federal Government spent more than $77.1 billion on IT procurement, and that number is projected to grow higher by the close of 2011.[^3] This is not a recent trend. Over the past decade, federal IT spending has swelled nearly seventy percent, up from $45.6 billion in 2001, 3 for a total bill of more than $500 billion.4 This growth is partially a result of the unfortunate fact that as few as nine percent of projects are delivered on budget and on time.5 The Government Accountability Office (GAO) reports that roughly forty-eight percent of all IT projects must be rebaselined, 6 and of those rebaselined projects, fifty-one percent must be rebaselined a second time.7

Compounding the problem, end users fail entirely to use nearly forty-five percent of features procured and rarely use another nineteen percent of those features.8 Thus, purchasing agencies ultimately use only about one-third of all features paid for by American tax dollars.9 In the end, nearly forty-five percent of federally procured software features ultimately fail to meet the user’s needs.10 It is therefore no surprise that the Secretary of the Department of Defense (DoD) Robert Gates called federal IT procurement “baroque.” 11 Too often IT procurement requirements are crafted with the input of neither end users nor product developers.12 As Office of Management Budget (OMB) Director Peter R. Orszag noted, federal IT projects cost more than they should, take longer than they should, and often fail to meet agency needs.13 Today’s federal regulations shackle government agencies to outdated project management practices and prevent them from harnessing the true power of IT innovations, which have far outpaced the laws that govern them.14

To better embrace innovation and respond to changing organizational needs, the Government must embrace a two-pronged approach involving both regulatory reform and top-down support for best-practices education to empower IT-procuring agencies to pursue more agile software development methods. By requiring that detailed specifications be outlined at the onset of the process, government procurement regulations encourage the less flexible, waterfall development techniques, rather than the more modern, agile development approaches used by the private sector today.15 While most prior attempts to reform federal IT procurement focused solely on statutory changes, 16 this Note proposes more modern project management practices and argues for top-down reform on both a regulatory and a human level.

I. Background — Waterfall v. Agile

Two primary schools of thought exist regarding software development practices: waterfall and agile software development. While today’s contracting regulations may propel agencies to use waterfall development, changes in industry practice with regard to large IT projects demands a government push toward more agile methodologies.

A. Waterfall Software Development Sees Modern Software Development as an Extension of its Traditional Engineering Roots

The traditional approach, “waterfall” software development, 17 seeks all requirements and specifications up front, distinguishing design and analysis from construction and development.18 Waterfall development techniques trace their roots to long-standing engineering fields such as architecture and electrical engineering.19 In such fields, late changes are costly and rigid requirements are a practical necessity.20 With the rise of software development in the latter half of the twentieth century, engineers applied the same methodology to developing computer software.

Despite their similar roots, traditional engineering is not a perfect metaphor for software development.21 First, unlike traditional engineering fields, software development benefits from nearly negligible switching costs.22 Second, the bulk of most software development projects is design and system architecture, a process requiring creative and analytical, rather than technical talent.23 In a world of widely adopted industry conventions, the creative necessities of a large-scale procurement project’s information architecture often overshadow technical necessities.24 Third, because software development regularly prioritizes designing ideal workflows and simplifying human interactions rather than embracing a formulaic science, such creative processes cannot easily be planned or predicted.25 In light of these industry trends, modern software development has recently embraced a more integrated practice known as agile software development.26

B. Agile Software Development Mitigates the Risk Inherent in Uncertainty by Approaching a Project as Multiple Independent Tasks

Agile development adopts an incremental approach to software development, but it does not seek to build software systems in a sequential, step-wise manner. Instead it recognizes the reality that a future system owner may be unable to gather all requirements up front.27 Even if this were possible, those requirements likely would change over time to reflect shifting technological and organizational priorities.28 Thus the project is broken down into several smaller components.29 Plans are continuously inspected and adapted to the empirical reality of the project through rapid prototyping.30 As a practice widely used in the private sector, empirically agile development delivers better performing projects on time and under budget.31

C. Modern Trends in Both Governance and Technology Push Federal Procurement Towards Agility

Today’s government IT landscape reflects a purposeful march toward privatization.32 Growing budget deficits in recent decades have rendered the Government anxious to deliver smarter, more cost-effective services to its citizens.33 In addition advances in hardware and technology, the Government’s approach to building complex, national systems has also evolved from the stand-alone computer systems of the 1960s, to the networked stovepipes of the 1970s and 1980s, to the glued-together middleware systems of the 1990s, and finally to the present day disaggregated, service-oriented architecture model.34 In a setting like today’s, mission-critical applications are distributed across multiple, loosely-coupled systems that communicate freely with one another, 35 allowing for rapid development and repurposing of investments.36 Despite advancing industry approaches to large IT projects, by forcing all requirements to be outlined upfront, federal procurement regulations continue to lock agencies into large, single-pass procurements.37

II. Despite its Advantages and Long-Standing History, the Rigidity of Traditional Software Development Bears Risks Disproportionate to its Returns

Traditional software development methodologies, commonly known as waterfall software development, are defined primarily by a sequential process 38 consisting primarily of two distinct stages: analysis and coding.39 The analysis stage, which in some situations can span months or even years, 40 asks prospective system owners to outline all conceivable requirements in a rigidly structured process before formally giving the requirements documentation to a software development team.41 The development team then completes a prolonged development cycle, fulfilling the specifications the customer described in the requirements documentation.42 Following this cycle, stakeholders and developers come together (for the first time) to verify that the software meets all initial specifications.43 These five steps are traditionally understood as the typical waterfall framework completed over the course of the procurement system.44 While waterfall development provides many advantages in the federal contracting environment, it also introduces many shortcomings both conceptually and practically.

A. The Rigidity of the Waterfall Process Brings Several Advantages to Federal IT Procurement

In both form and function, waterfall development mirrors current procurement models. The first step requires that future system owners document their needs extensively, and such requirements are easily incorporated into a solicitation. This up-front documentation allows agencies to safely budget funds and allows contracting officers (COs) to marry funds to specific, predefined contractual events. “Phase gates” within the contract provide agencies objective standards to evaluate a project’s propensity for success and allow agencies to abandon projects in some instances when the prospect of successful delivery appears grim. Within an agency, waterfall development requires COs to justify projects to stakeholders early in the development cycle, and this overall process has gained agencies’ tacit endorsement over the years.45 By nature of its formal requirements, waterfall software development leaves behind it a wake of documentation, the lifeblood of bureaucracy.

B. Waterfall Software Development Fails to Adequately Respond to the Ever-Changing Conditions that Make Up a Project’s Problem Space

Despite its long-standing history, waterfall software development comes with shortcomings. The outdated methodology assumes requirements can be predicted upfront. As a result it fails to adequately respond to changing conditions and forces agencies to incur costs disproportionate to project returns.

i. Both conceptually and practically, waterfall assumes that contracting agencies can accurately forecast a project’s requirements in advance

Waterfall relies on two key assumptions: (A) That requirements are fully understood by both contractor and contracting agency, and (B) That requirements are unlikely to change.46 Yet due to the often-unique nature of government systems, software contractors typically face challenges to which they have never been exposed, rendering predicting of future needs an inherently futile task.47

The traditional procurement model, which leans heavily on waterfall’s central tenants, demands specificity in planning, funding, and acquisition, and requires the contractors and COs to attain a certain level of “predictive precision” simply not found in the ever-changing world of technology.48 As such, by requiring that all specifications be outlined upfront, the current procurement model encourages agencies to attempt an inevitably unsuccessful endeavor and thereby increases project risk.49

The unrealistic premises of waterfall procurement create a snowball effect. Because it is impossible for COs to resolve all unknowns at the onset of a procurement, they often err on the side of caution and compound errors by over-documenting requirements and making erroneous assumptions.50 This risk is further exacerbated as a result of waterfall’s insistence on delaying testing until late in the development cycle, 51 meaning mistakes often do not become apparent until corrections are cost-prohibitive.52 Especially given the size of typical government procurements, “trying to implement everything at once increases the risk of failure on a grand scale if the technology fails to work as expected or if the original idea was misconceived.” 53 To function optimally, waterfall methodologies require both contracting parties to possess perfect information. This a practical impossibility when federal agencies acquire major IT systems.

ii. Waterfall development fails to adequately respond to change

A single-pass approach assumes that all variables remain constant throughout the contracting process.54 Yet experts and lay consumers alike know that technology slowly nudges even the most recent purchases toward obsolescence. Despite this, government bureaucracy is, by design, a time consuming and cumbersome endeavor.55 Under waterfall, because design is distinct from development, development necessarily occurs in isolation from management efforts.56 Requirements are not permitted to change throughout the process, regardless of the practical or technical realities of the agency’s needs.57 Ultimately, technology and the needs of the contracting agency often outpace the procurement process itself.58

If partway through the procurement process a superior new technology emerges or an agency reevaluates its requirements and decides its needs have changed — a not-too-distant reality given the span of multi-year procurements — the contractor is both disincentivize and contractually prohibited from adapting accordingly.59 Traditional approaches to procurement treat any deviation from the contract’s initial requirements as a failure on the contractor’s part and risk the contracting agency withholding payment.60 In a sense, waterfall equates software development to Ford’s assembly line, but in this case the conveyor belt moves so slowly 61 that the product is obsolete by the time it is ready for delivery.62 In the context of long-term projects, waterfall’s quest to eliminate uncertainty at all costs creates the risk that when delivery finally occurs, what is delivered may no longer meet the agency’s needs.63

iii. Waterfall development provides a return disproportionately less than its significant administrative cost

The documentation requirements of waterfall impose an unnecessary burden on agencies. Agencies often spend as much as two years making project assumptions, 64 defining requirements, and developing cost-and-time estimates.65 Today, detailed requirement-gathering has become a discipline in and of itself, which is wholly separate from system-development 66 and is often contracted out by the Government.67 Traditional software development requires a one-direction, time-delayed information flow 68 that is inherently inefficient.69 This waterfall software development inefficiency requires contracting agencies to invest significant amounts in outlining specifications, often forcing those agencies to hire more contracting specialists, technical experts, consultants, and managers than actual software developers.70

III. Given its More Effective Response to Change, Agile Software Development Can Deliver Better Performing Projects More Quickly and Cheaply than Waterfall

Agile development mitigates many of the risks imposed on agencies by waterfall development. Agile represents an iterative approach to software development that prioritizes communication over documentation and that adapts to change rather than futilely attempting to predict it. As a result, agile projects tend to be more efficient, less costly, and more predictable than their waterfall counterparts.

A. The Ability to Rapidly Respond to Change is the Shibboleth of an Agile Project

At its most fundamental level, agility is the ability to quickly and effectively respond to change.71 Agile software development came about in the mid-1990s as an alternative to heavyweight approaches’ tendency for budget overruns.72 Whereas waterfall requires an “over the fence” approach, by delaying decision making, agile software development embraces an “I’ll know it when I see it” mentality.73 As a result, agile software development presents agencies with three key advantages over the traditional waterfall approach to IT procurement, in that agile software development prefers: (i) many short development cycles over a single pass; (ii) person-to-person communications over up-front documentation; and (iii) adapting to changing needs i

i. Agile is iterative, breaking long-term projects into multiple independent, manageable tasks

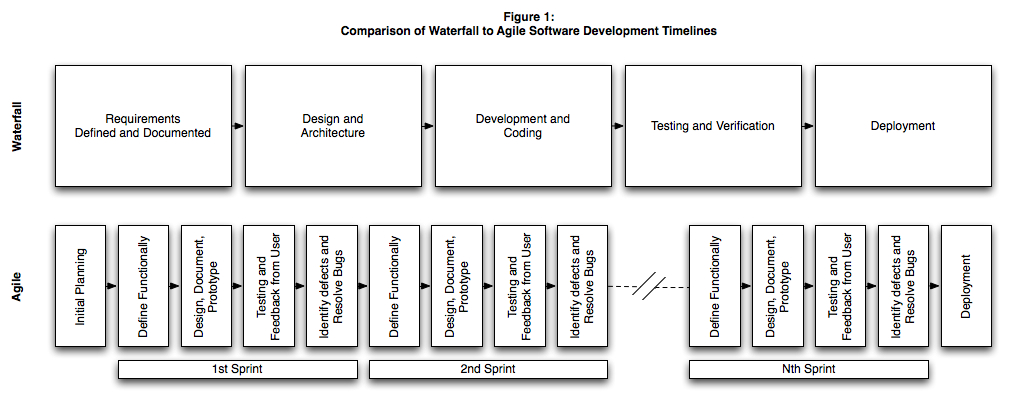

Figure 1 - Agile and Waterfall Development Cycles Compared (PDF)

Agile development can be thought of as the amalgamation of many short waterfall development cycles.74 An agile project consists of multiple coding sprints, commonly known as iterations, in which tasks are chosen from an ongoing feature backlog 75 and become realized early on through rapid prototyping and testing.76 “An iteration produces a small, tested, integrated increment of business value that is validated by customers and used as feedback for the next iteration. Iterations occur at short, regular intervals and they involve everyone: from architects to testers to the help desk staff.” 77 Agile methodologies see the process as dynamic, evolving, and organic, rather than static, predefined, and mechanistic.78 Agile breaks a system into smaller, more fungible chunks of immediate value to the user, rather than attempting a software development project as a single, undivided task.79

ii. Agile prioritizes communication and collaboration over documentation and structure

To facilitate agile’s hallmark rapid delivery in place of time-consuming formal documentation and rigid structure, agile relies on extensive person-to-person communication and organic processes. In simplest terms, agility is defined by a software team’s ability “to efficiently and effectively respond to and incorporate requirement changes during the project lifecycle.” 80 To achieve this goal agile focuses on collaboration rather than documentation. Agile promotes frequent, continuous delivery of working software and embraces changing requirements through close collaboration, self-organizing and self-motivated teams, face-to-face communications, and in turn, continuous adaptation.81

In practical terms, agile values individuals and interactions over processes and tools, working software over comprehensive documentation, customer collaboration over contract negotiation, and responding to change over following a plan.82 Because agile prioritizes one-on-one communication over formal documentation, unnecessary documentation is wholly alleviated and overhead costs are reduced.83 In addition, requirements tend to be more concrete and clearer and to produce a better final product.84 Given that project teams undertake smaller projects under an agile framework, systems can be delivered without the sluggishness inherent to waterfall projects.

iii. Agile is adaptive rather than predictive

Traditional engineering methodologies emphasize rigid planning and forecasting.85 By contrast, agile embraces the philosophy that requirements are discovered through use and refinement.86 As requirements emerge organically during the software development process, 87 they evolve as stakeholders gain a deeper understanding of the project and their needs.88 Put differently, by delaying decisions to the last possible moment, the agile model allows agencies to make decisions “based on facts rather than forecasts.” 89 This provides several distinct advantages over traditional waterfall methodologies.

B. By More Effectively Responding to Change, Agile Methodologies Can Offer Agencies Greater Predictability and More Timely and Less Costly Project-Delivery

Agile projects more readily adapt to change and are delivered on time and for less cost, ensuring a high degree of predictability.

i. Agile development adapts to change

By delaying irreversible decisions until later on in the procurement cycle, agile’s incremental and iterative framework allows teams to rapidly respond to the empirical realities of a project through continuous evaluation of project plans.90 Following each short coding sprint, agency stakeholders are presented with the ability to reevaluate each desired function’s relative priority, and the subsequent coding sprints adapt to embrace those shifting requirements.91 Agile’s multiple, rapidly executed increments allow stakeholders to specify more easily defined objectives, rather than abstract technical requirements.92 Agile’s evolutionary approach embraces early, successive prototyping, and thus produces timely working releases that meet stakeholders’ needs.93 This approach is particularly useful in the Federal Government’s modular, service-oriented architectures.94 Agile’s iterative approach in the end allows projects to more accurately and more immediately meet agency needs.

ii. Agile development is more efficient than waterfall development

In the context of large-scale government projects, agile can deliver systems sooner than its similarly sized waterfall counterparts.95 Agile software development is more efficient than traditional development methodologies for five key reasons: First, agile allows development teams to begin work immediately, even before requirements are fully known, an impossibility under a waterfall contract; 96 second, whereas waterfall development uses multiple factors to prioritize tasks, agile focuses solely on maximizing business value, 97 and thus, high-priority goals are realized and delivered to the customer early on; 98 third, because agile communicates concrete specifications via face-to-face discussions, rather than lofty goals through formal documentation, and because agile embraces a streamlined decision-making process, rather than a rigid hierarchical structure, development teams gain a better understanding of and produce products that better meet agency needs and requirements; 99 fourth, agile promotes the end user’s involvement throughout the process and thus ensures early and constant validation of features, minimizing the need for costly and time-consuming pre-deployment changes; 100 finally, because agile’s continual validation model requires constant use of the procured system, users receive training and preparation to use the new system on day one.101 For all of these reasons, agile is more likely to deliver projects on time.

iii. Agile is inherently less costly than waterfall

Agile projects tend to be less costly overall for three primary reasons. First, because COs do not have to spend extensive time pre-award defining project requirements, agile development inherently imposes a lesser administrative burden.102 Face-to-face communication may require less investment than extensive documentation, in so far as in-person communications facilitate prompt clarification of any discrepancies or misunderstandings. Second, administrative costs are further reduced as the need to modify the original contract if requirements change is wholly eliminated.103 Finally, once the agency has awarded the contract, because agile breaks the project into smaller, more approachable tasks, agile reduces cost and cycle time by better utilizing the contractor’s resources.104 As a result, agile more consistently delivers projects on or under budget more often than waterfall.

iv. Agile is predictable

While at first glance agile may seem less predictable, decreasing the amount of speculation involved in decision making inherently increases the predictability of the final outcome.105 Unlike waterfall’s hands-off approach, small increments of constant feedback provide a safety net of predictability upon which the contracting agency can base its decisions.106

C. Despite its Advantages, Agile Methodologies Present Contracting Officers With Several Key Challenges

Agile’s define-as-you-go approach does not often lend itself to satisfying government documentation requirements. Its lack of pre-award specificity makes costs difficult to estimate, and, when compared to waterfall, agile exposes the contracting agency to greater risk.107

i. Agile methods are not well suited to meet government documentation requirements

Extensive government contracting documentation and reporting requirements impose the greatest barrier to the adoption of agile procurement in the U.S. Traditional government contracting requires that project “artifacts” be generated at each step of the process to memorialize project activity.108 Agile projects, on the other hand, forgo formal paperwork.109 Yet agile is not necessarily incompatible with these procurement requirements. Although there is no perfect alternative to reporting progress to plan, in most cases, agencies can use earned value project management to reconcile the two schools of thought.110 More difficult, agile methodologies can be reconciled with formal documentation requirements at the solicitation stage.

ii. Agile engenders a lack of specificity pre-award, rendering cost estimates difficult to calculate

Agile does not require that potential systems outline technical specifications owners before contract award, potentially causing COs difficulty as they attempt to estimate project costs.111 Often, project timelines are at best only roughly defined, and project teams may change drastically as requirements change.112

However, while it may allow for less specificity pre-award, agile constantly adapts to the actual needs of the project (rather than remaining true to initial projections). As a result, in the long run, agile provides more accurate cost metrics and greater budget fidelity overall.

iii. Agile offers contracting agencies less risk-avoidance upfront

As a risk-avoidance measure, government contracting requires extensive reporting and detailed paper trails to accompany each step of the procurement process.113 By integrating the contractor and contracting agency, agile development forces both to share the burden of risk.114 Yet, while agile offers less risk avoidance up front, by integrating both the contractor and the contracting agency early on, it reduces the overall level of risk.115

IV. Current Regulations and Agency Practices Restrict Adoption of More Efficient Agile Methods

Current procurement practices restrict the Government’s ability to adopt the agile model. The structure of the contracting process often conflicts with agile’s central tenants, and even if this basic incongruence is overcome, government contracting embodies a culture averse to agile.

A. The Structure of Traditional Government Contracting is Not Amenable to Agile Development Methods

For three reasons, government contracts are not written for agile.116 First, as a matter of public policy, government contracting typically requires agencies to prefer competition at the cost of project deliverables.117 Second, government programs generally involve significant lead times – forcing funding to be mapped out well in advance – rendering a “develop as you go” method counterintuitive.118 Finally, most contract vehicles call for stable requirements, a method inherently incompatible with an adaptive model.119

B. Government Procurement Embodies a Culture Averse to Agile Methodologies

Government procurement embraces an entrenched culture of rigid parameters, documentation, and meticulously defined processes.120 This manifests itself in several forms. For one, government budgeting focuses on projects that fall within a single budget year, are controlled by a single budget program, and promise an easily predicted, low-risk return.121 Additionally, at the most basic level, it is not agencies who procure IT but rather individuals on behalf of those agencies. As in any sector, these individuals’ incentives may not align with their employer’s goals. A CO who chooses an innovative but ultimately flawed contracting vehicle may face termination or reprimand, and without specific financial incentives, may gain nothing if the innovation proves beneficial.122 Thus even if federal acquisition regulations on paper allow for agile development, in practice, COs have an incentive to avoid the near-term risk presented by innovation.123 Third, new ideas must compete against proven ones and “urgent needs […] take precedence over [future] possibilities.” 124 High-value but high-risk ideas like agile require support from upper management to take hold, and this support by-and-large does not exist.125 Finally, across the board both COs and in-house IT departments are either unfamiliar with or unaccustomed to agile methods.126 Before agile’s adoption, significant cultural reform and education must take place on both an organizational and an individual level.

C. Current IT Procurement Methods are Not Amenable to Agile Development

Many IT contracting vehicles may exist in the context of any given project. While price-directed bids, competitive negotiations, conceptual negotiated sourcing, engineering selection, and modular contracting may provide some promise, no existing contracting vehicle is fully compatible with agile methodologies.

i. Price directed (sealed bid)

Where bids are solicited and chosen solely based on cost, traditional acquisition takes the form of price-directed or sealed bid procurement.127 This model does not accord with agile in that it requires precisely defined requirements in advance of solicitation.128 Additionally, such technical requirements crowd out many private sector firms and spawn a government-specific industry that limits competition and available resources.129

ii. Competitive negotiations

A negotiated procurement model allows contracting agencies to solicit proposals, similar to the price-directed model.130 Unlike the price-directed model, however, bids are not sealed and agencies are permitted to discuss deficiencies with firms, which may then resubmit their bids.[^132] Nevertheless, the negotiated procurement model still requires the agency to outline technical specifications up front, making it incompatible with agile methods.

iii. Technology/Conceptual Negotiated Sourcing

Technology or conceptual negotiated sourcing is a two-phase model. First the contracting agency awards the initial phase of design and conception to multiple competing bidders through multiple small-dollar, short-term contracts.131 The agency then selects its preferred plan from among the submissions and continues with the procurement as if it were a sealed bid.132 This approach is not ideal from an agile perspective, as it lengthens the time for which major resources are committed and delays prototyping until multiple firms can submit project plans.133 This approach is also less efficient, as it forces the Government to fund parallel development and planning efforts.134 For the federal IT procurement to better embrace innovation, change is needed.

iv. Engineering Selection under the Brooks Act

Under the Brooks Act, 135 initially intended for traditional engineering fields, agencies may use a two-phase negotiated procurement model to procure systems that may justifiably be performed by engineers.136 In the first phase, following a solicitation, competing firms submit proposals outlining methodology and techniques.137 Purchasers evaluate and rank proposals based not on price but rather on each firm’s unique qualifications, performance history, and likelihood of delivering a final product that meets agency needs.138 From these rankings, the purchasing agency generates a “short list” and requests more detailed proposals from the top-ranked firms before making a final selection.139 Despite the engineering provision’s compatibility with agile, however, contracting agencies are statutorily prohibited from using the seemingly ideal contracting vehicle when procuring software.140

v. Modular Contracting

Section 5202 of the Information Technology Management Reform Act of 1996 (ITMRA) 141 encourages agency heads to use modular contracting when acquiring major information systems.142 Designed to transform federal IT acquisitions into a results-oriented procurement system, 143 under modular contracting, complex systems are disaggregated into several discrete, interoperable services and procured accordingly.144 To “reduce program risk and incentivize contractor performance while meeting the government’s need for timely access to rapidly changing technology,” 145 ITMRA Section 5202 states that agencies should “to the maximum extent practicable” use modular contracting to acquire major systems, and may use modular contracting for all other systems.146 The Act notes that modular contracts are easier to manage, have an increased likelihood of success when implementing complex systems, mitigate risk through compartmentalization, and allow subsequent increments to take advantage of advances in technology.147 In its traditional form, however, modular contracting still requires that specifications be known and documented prior to each module, and thus is not fully compatible with agile methods.148

By forcing requirements to be outlined at the onset of the process, the procurement vehicles outlined above force contracting agencies to use outdated development methods and help to perpetuate the stereotype that government systems are overpriced, inefficient, and obsolete at the time of delivery.

V. Significant Reform is Necessary to Allow Federal IT Procurement to Take Advantage of Industry Advances that Have Far Outpaced Laws Intended to Govern Them

For the Federal Government to become more agile, three distinct but parallel initiatives are necessary. First, COs and technical representatives must be educated as to the best practices for implementing agile in government contracting. Second, statutory requirements encouraging agencies into waterfall frameworks by demanding extensive requirements documentation pre-award should be avoided through alternative contracting vehicles. Finally, even if permitted by law, proponents must garner significant top-down support from within their agencies for agile practices to be accepted.

A. COs and COTRs Require Education Before Agile Can be Introduced to the Federal Contracting Environment

Before federal IT procurement can embrace agile methodologies, best-practices education is required on two levels. First, COs must learn best practices for agile contracting. Second, technical officers within the agency must learn best practices for agile project management in the government sector.

i. COs must learn best-practices in agile contracting

Many COs may not know what agile development is, let alone that it is a potential contracting vehicle and how best to implement it. The White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) should oversee the joint efforts of the General Services Administration (GSA), the White House OMB, 149 and the Office of Federal Procurement Policy (OFPP) to educate COs as to agile contracting best practices.150

Solicitations should outline functional rather than technical requirements 151 and should be crafted without the significant lead time often characteristic of government procurement. The statement of work should specify high-level goals or systems, rather than specific features, and these goals should eventually become the framework that defines each subsequent sprint. The contract should also include specific, functional milestones and accompanying deadlines, which may also be married to an award schedule.

ii. Agency technical contacts (COTRs) must learn best practices in agile project management

Alongside existing professional development efforts, contracting organization technical representatives must be trained in best practices for executing and managing development projects through an agile framework. This may include formal workshops for employees; the recruitment of experienced, private sector project managers; or simply a push to increase awareness of agile methodology and educational resources already at agencies’ disposal.

B. Existing Procurement Requirements Demand Extensive Documentation Up Front, Forcing Agencies into Agile Frameworks

Even if an agile-friendly contracts are prepared, executed, and overseen successfully, two statutory stumbling blocks may hinder agile’s adoption: (i) the solicitation and subsequent award of the contract; and (ii) the governance of the contract while it is in progress.152

i. Engineering services, FAR Part 36

The single largest statutory roadblock to agile-friendly contracts is the requirement for technical specifications prior to solicitation. This requirement locks contracting agencies into a waterfall method post-award and is antithetical to agile methodologies. To pursue an agile framework, agencies should establish functional rather than technical benchmarks, developing a framework that can be used to define the focus of each subsequent sprint.

Part 36 of the FAR provides a modified procedure for procuring architectural and engineering services.153 Such a procurement would follow a two-phase procedure. In phase one competing firms would submit proposals including their technical approaches and technical qualifications, but these would not include detailed design information or cost or price information. Agencies would then rank the top firms, which would be asked to submit detailed proposals before the winning firm was selected for a contract to be executed through the design-build framework.154

Under FAR 36.601(4)(a)(3), to be eligible for the architecture-engineering route, the acquisition must “logically or justifiably require performance by registered architects or engineers or their employees.” 155 Congress should expand the definition of this section to include computer and software engineers to allow IT procurement to follow this route.

ii. Modular contracting, FAR Part 39

FAR 39.103 allows agencies to break large acquisitions into several smaller acquisition increments.156 To aid in accounting, budgeting, and documentation, an agile procurement can be contracted as one overarching contract defining the scope of the work and outlining a schedule by which each sprint’s focus will be defined. This large contract may incorporate smaller contracts for each subsequent sprint, if necessary, as part of a process wholly in line with the Government’s push toward system-oriented architectures.

C. COs Lack Top-Down Support for IT Procurement Reform

The above goals cannot be realized without significant top-down support from the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy, OMB, and Chief Technology Officers at each agency. COs must be empowered to take risks with such an unconventional approach. While top administration officials have made statements supporting an agile approach to IT procurement reform, such rhetoric remains noncommittal. Tangible, specific guidance from senior administration officials to agency CIOs and CFOs must occur in order for innovation to succeed.

VI. Conclusion

The federal IT procurement system is outdated. Projects are consistently delivered late, over-budget, and obsolete. Much of this trend can be traced back to flawed legal frameworks that lock agencies and contractors into an outdated development model. Through education, reform, and organization-wide support, federal agility can become a reality. Any computer user knows that as systems age they begin to slow. Today, the federal IT procurement system is running slowly, to the detriment of both agencies and the public, and it is long overdue for a system-wide upgrade.

Originally published in The Public Contract Law Journal, Volume 41, Issue 1. Available for public use under a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA license.

-

This holds true for both civilian and military procurement systems. See generally Office of the Under Sec’y of Def. for Acquisition, Tech., and Logistics, Report of the Defense Science Board Task Force on Department of Defense Policies and Procedures for the Acquisition of Information Technology (2009) [hereinafter DoD Acquisition Report]. ↩

-

Jay P. Kesan & Rajiv C. Shah, Shaping Code, 18 Harv. J.L. & Tech. 319, 373 (2005). ↩

-

Id. ↩

-

White House Forum on Modernizing Gov’t, Overview and Next Steps 5 (2010). ↩

-

Victor Szalvay, Danube Techs., Inc., An Introduction to Agile Software Development1 (2004). ↩

-

DoD Acquisition Report, supra note 1, at 44. “Rebaselining” occurs when modifications are made to a project’s baseline, for example, its cost, schedule, and performance goals, to reflect changed development circumstances. U.S. Gov’t Accountability Office, GAO-08–925, Information Technology: Agencies Need to Establish Comprehensive Policies to Address Changes to Projects’ Costs, Schedule, and Performance Goals 2, 13 (2008). Changes in requirements and objectives (scope creep) was the most commonly cited reason for rebaselining. ID. at 8. ↩

-

Id. ↩

-

Szalvay, supra note 6, at 8. ↩

-

Id. ↩

-

Gwanhoo Lee & Weidong Xia, Toward Agile: An Integrated Analysis of Quantitative and Qualitative Field Data on Software Development Agility, 34 MIS Q. 87, 88 (2010). ↩

-

Robert Gates, A Balanced Strategy: Reprogramming the Pentagon for a New Age, Foreign Aff., Jan./Feb. 2009, at 28, 34. ↩

-

See Vivek Kundra, U.S. Chief Info. Officer, White House, 25 Point Implementation Plan to Reform Federal Information Technology Management 17 (2010) (calling for “increased communication with industry” and “high functioning, ‘cross-trained’ program teams”). ↩

-

See Memorandum from Peter R. Orszag, Dir. of Office of Mgmt. and Budget, Exec. Office of the President, to Heads of Exec. Dep’ts and Agencies 1 (June 28, 2010) [hereinafter Orszag Memorandum] , available at http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/omb/assets/memoranda_2010/m-10–26.PDF ↩

-

These inefficiencies are troubling, not only because they represent a significant financial cost to the taxpayer, but also because they undoubtedly represent a significant cost to the realization of agency goals. See Stanley N. Sherman, Government Procurement Management 30 (1991). As President Barack Obama recently noted at the White House Forum on Modernizing Government, “when we waste billions of dollars, in part because our technology is out of date, that’s billions of dollars we’re not investing in better schools for our children, in tax relief for our small businesses, in creating jobs and funding research to spur the scientific breakthroughs and economic growth of this new century.” Attachment B: President’s Remarks, in White House Forum on Modernizing Government: Overview and Next Steps 17, 18 (2010), available at http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/omb/assets/modernizing_government/ModernizingGovernmentOverview.PDF. ↩

-

DoD Acquisition Report, supra note 1, at 16–17 (noting many large corporations have gained a significant advantage from using agile). See White House Forum On Modernizing Gov’t, Overview And Next Steps 9 (“Federal IT projects are too often marked by milestones spaced too far apart.”). See generally infra Parts III-IV*.* ↩

-

See Ralph C. Nash, Jr., Solutions-Based Contracting: A Better Way To Buy Information Technology?, 11 Nash & Cibinic Rep. ¶ 17, at 60 (Apr. 1997). ↩

-

A more in-depth examination of the characteristics of waterfall development is discussed infra part II. ↩

-

Adrian Royce, Agile in Government: Successful On-Time Delivery of Software 1, in Conference Papers, 20th Australian Software Engineering Conference (2009). ↩

-

Martin Fowler, The New Methodology, Martin Fowler (Dec. 13, 2005), http://www.martinfowler.com/articles/newMethodology.HTML. ↩

-

For example, an architect draws up blueprints for a house and hands them off to a contractor for construction. Should the future homeowner decide after the fact that he wishes to deviate from his original plan, for example, he prefers the kitchen be five feet wider, such a change would incur substantial time, labor, and material costs as floors are re-laid, pipes re-plumbed, and electrical outlets rewired accordingly. ↩

-

Initially the application of the traditional methodology to the emerging field was much more straightforward. Room-sized mainframe computers required users to painstakingly code instructions on physical cards, submit them to be processed in batches, and await the result. James O. Coplien & Gertrud Bjørnvig, Lean Architecture: For Agile Software Development, 218 (2010). Today, however, advances in technology and the personal computer have allowed the software development environment to embody an interactive process whereby software engineers can receive immediate feedback as to their software’s success or failure. ID. at 218–19 (noting that originally high computing costs drove up the cost of mistakes such that “rigid disciplines ruled.” Today, mistakes are cheap.). ↩

-

Fowler, supra note 20. If a federal agency decides that the navigation menu on its new site should be five pixels larger, to make such a change would simply require modifying one or two values in the website’s source code, an insubstantial labor cost in a large government contract. ↩

-

Id. ↩

-

Information architecture necessities can include the creation of user profiles (personas of hypothetical system users), use cases (an analysis of the tasks those users might perform), and wireframes (the visual layout of the system’s interfaces). ID. ↩

-

See Fowler, supra note 20. ↩

-

Mark Lycett et al., Migrating Agile Methods to Standardized Development Practice, Computer, June 2003, at 79, 79. ↩

-

Szalvay, supra note 6, at 2; Government Contracting for Software Development Course Manual 33 (1994) [hereinafter Course Manual]; Lan Cao & Balasubramaniam Ramesh, Agile Requirements Engineering Practices: An Empirical Study, IEEE Software, Jan./Feb. 2008, at 60, 64; Fowler, supra note 20 (noting engineers’ “nature is to resist change. The agile methods, however, welcome change”). ↩

-

Fowler, supra note 20. ↩

-

Szalvay, supra note 6, at 1–2; Cao & Ramesh, supra note 28, at 63. ↩

-

Cao & Ramesh, supra note 28, at 63. ↩

-

ID. Similarities can be drawn between modern software development and the Japanese auto industry forty years ago. Beginning in the 1970s Japanese auto manufacturers began adopting lean manufacturing practices to develop new vehicles. Michael A. Cusumano, Japanese Technology Management: Innovations, Transferability, and the Limitations of “Lean” Production 1 (Sloan Sch. of Mgmt., Mass. Inst. of Tech., Working Paper No. 3477–92, 1992). Due to this refined approach’s reduced overhead, Japanese manufacturers were able to generate thirty percent more profit per vehicle than Chrysler, one-hundred percent more per vehicle than Ford, and two-hundred percent more per vehicle than General Motors. Mary Poppendieck, Cutter Consortium Executive Report, Lean Development and the Predictability Paradox 1 (2003). When compared to Detroit’s traditional design and manufacturing practices, Japanese manufacturers produced higher quality vehicles in one-third less time. ID. While in the United States nearly half of all projects missed their target date, in Japan, all but one sixth hit the market on time. ID. Japan’s lean-manufacturing methods produced cheaper, more successful cars faster. ID. ↩

-

Darrell A. Fruth, Economic and Institutional Constraints on the Privatization of Government Information Technology Services, 13 Harv. J.L. & Tech. 521, 524–25 (2000). ↩

-

Id. ↩

-

DoD Acquisition Report, supra note 1, at 7. ↩

-

A detailed explanation of the evolution to a service-oriented architecture is beyond the scope of this Note, but in simple terms, if one thinks of information as a product, the evolution mimics the move from individual manufacturers producing a good, to a factory producing a good, to that factory adopting an assembly line approach. A government agency might build a system once, (for example, an application to calculate the appropriate census block based on a given address,) and then will have subsequent systems query that already-built application, rather than duplicate the functionality. Any given request for information may go through five, ten, perhaps even a hundred systems, each of which can be procured or upgraded individually. Interview with Greg Elin, Chief Data Officer, FCC & Michael Byrne, Chief Geographic Info. Officer, FCC, in Wash., D.C., (Mar. 11, 2011) [hereinafter FCC Interview]. ↩

-

ID.; Orszag Memorandum, supra note 14, at 1 (noting that “by setting the scope of projects to achieve broad-based business transformations rather than focusing on essential business needs, Federal agencies are experiencing substantial cost overruns and lengthy delays in planned deployments. Compounding the problem, projects persistently fall short of planned functionality and efficiencies once deployed.”). ↩

-

See Examining the President’s Plan for Eliminating Wasteful Spending in Information Technology: Hearing Before the S. Subcomm. on Fed. Fin. Mgmt., Gov’t Info., Fed. Servs., and Int’l Sec., 112th Cong. 3–4 (2011) (statement of Vivek Kundra, Fed. Chief Info. Officer, Office of Mgmt. and Budget) (noting that the current procurement model does not align well with the rapid pace of today’s technology cycle). ↩

-

Szalvay, supra note 6, at 1–2. ↩

-

Winston W. Royce, Managing the Development of Large Software Systems: Concepts and Techniques, in Proceedings of IEEE WESCON (1970), reprinted in Proceedings of the Ninth International Conference on Software Engineering 328, 328 (1987). ↩

-

Gen. Servs. Admin. Strategic Info. Tech. Analysis Div., White Paper: Modular Contracting 16, 8 (1997) [hereinafter Modular Contracting White Paper]. See Kundra, supra note 13, at 17 (noting “the acquisition process can require program managers to specify the government’s requirements up front, which can be years in advance of program initiation”); Orszag, supra note 14, at 2 (observing that “historically government IT projects have involved expansive, long-term projects that attempt to change almost every aspect of a business system at once… [and have] taken years, sometimes a decade, and have failed at alarming rates”). ↩

-

Course Manual, supra note 28, at 33. ↩

-

See W.Royce, supra note 40, at 328. ↩

-

ID. at 329. ↩

-

More formally, the standard waterfall process follows five distinct steps: (1) requirements are defined and documented, (2) the system is designed and architected, (3) development teams code the software, (4) the software is tested and validated against the requirements from step one, and finally (5) the system is deployed. See ID. at 328–29. ↩

-

Richard K. Cheng, On Being Agile, NextGov, Sept. 23, 2010, http://www.nextgov.com/nextgov/ng_20100923_7965.php. ↩

-

Szalvay, supra note 6, at 1–3; Course Manual, supra note 28, at 33. Such an approach makes sense when it is traced backed to its traditional roots. Engineers building bridges rely on well-established laws of physics supported by the fundamentals of mathematics, two sciences that are rigidly defined and easily relied upon. Software development, on the other hand, is not bound by the rules of the physical world. Gravity, an assumed constant in engineering, has relatively little relevance to programming. ↩

-

See Mark Leicester, Government Projects the Agile Way: Can It Be Done?, St. Services Commission (Apr. 16, 2009). ↩

-

Modular Contracting White Paper, supra note 41, at 7; Cao & Ramesh, supra note 28, at 63. See Further Details on Modular Contracting Left for Public Meeting–Proposed Rule Adds Little to Clinger-Cohen Act, 39 Gov’t Contractor ¶ 161, Apr. 2, 1997 [hereinafter Further Details]. ↩

-

Modular Contracting White Paper, supra note 41, at 7 (noting that “forcing this rigidity into the systems development acquisition process – intending to minimize risks and mistakes – can actually exacerbate the same.”). As FCC Geographic Information Officer Michael Byrne commented, “procurement is like a board game. You are trying to move your pieces to the other side. This would be easy if you had no opponent. When the other team begins moving forward there’s no way to… know how to optimally get to the other side, and waterfall software development expects just that. Data changes, technology changes, policy changes, governance changes – this is the opposing player – and there’s no way to predict the interaction with my pieces.” FCC Interview, supra note 36. ↩

-

Sherman, supra note 15, at 210–11; Poppendieck, supra note 32, at 1, 5 (arguing “the more companies attempted to define the process of product development, the less the organization was able to carry out that process”). ↩

-

Further Details, supra note 49. ↩

-

Id. ↩

-

ID. Consider the process of documenting the requirements to develop a BlackBerry or iPhone. Both mobile phones are roughly 3×5, square with rounded edges, black, have a keypad and on/off switch, make calls, send and receive email and text messages, browse the internet, and have downloadable applications. On paper they are identical. It is difficult to objectively describe, for example, “intuitive interface.” Prototyping is the vocabulary agile uses to solve this problem. FCC Interview, supra note 36. ↩

-

Szalvay, supra note 6, at 1. ↩

-

Audio recording: Removing Barriers to Organizational Agility, George Washington University Tech Alumni Group Federal Executive Round Table (Nov. 4, 2010) [hereinafter Federal Executive Round Table] (on file with author). ↩

-

Id. ↩

-

Id. ↩

-

ID.; Kundra, supra note 13, at 17 (observing “the lag between when the Government defines its requirements and when the contractor begins to deliver is enough time for the technology to fundamentally change”). ↩

-

Federal Executive Round Table, supra note 56. ↩

-

Modular Contracting White Paper, supra note 41, at 13. ↩

-

A prime example of such a phenomenon is the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (PTO). In 1983 the PTO initiated a billion-dollar automation effort using waterfall. At the time the PTO’s patent files contained some thirty-three million documents, supporting patents issued since 1790, and grew at the rate of approximately one million documents per year. The goal was to have a fully deployed system by 1990, however by 1987, the PTO began to realize that the program was fatally behind schedule and switched to an agile approach. Course Manual , supra note 28, at 66–67. The PTO was able to successfully deploy its patent search system (CSIR) later that year, and by 1992 had a significant portion of its automation system integrated into its workflow. U.S. Gov’t Accountability Office, GAO/AIMD-93–15, Patent and Trademark Office: Key Processes For Managing Automated Patent Development Are Weak 4 (1993). ↩

-

See generally Szalvay, supra note 6, at 1. The ability to adapt to change has implications beyond project efficiency as well. Hackers, cyber terrorists, and other malcontents are not bound by the rigidity of waterfall and are often able to adapt more rapidly to government countermeasures than the Government can develop defenses. See Federal Executive Round Table, supra note 56. Similarly, after spending nearly two years and 0 million dollars developing handheld computers for use in conjunction with the 2010 census, the U.S. Census Bureau was forced to drop its plans and revert to paper-based collection when it realized the waterfall approach it had adopted would not deliver a working system in time for the census data collection. White House Forum, supra note 5, at 5–6. ↩

-

The Federal Communications Commission recently procured the National Broadband Map using an agile framework. Within six months, the agencies had a working prototype, and six months following that, a final product. Less than ten percent of the project’s total funding was used to make a prototype, the source code of which being distributed alongside the project’s RFQ. The contract’s first deliverable was requirements documentation outlining a project management plan, but daily scrum meetings provided both agency and contractor the opportunity to revise requirements. FCC Interview, supra note 36. ↩

-

Project assumptions might typically include the format of input data, deadlines, technology, policy, or governance. FCC Interview, supra note 36. ↩

-

Modular Contracting White Paper, supra note 41, at 7. ↩

-

Poppendieck, supra note 32, at 6. ↩

-

Sherman, supra note 15, at 222–24. ↩

-

While documentation may memorialize requirements, the act of documentation delays the information’s communication and prevents meaningful dialog regarding the project specifications. ↩

-

Poppendieck, supra note 32 at 6. ↩

-

Federal Executive Round Table, supra note 56. ↩

-

Lee & Xia, supra note 11, at 88. ↩

-

ID. at 89. ↩

-

Szalvay, supra note 6, at 3; Poppendieck, supra note 32, at 11–12. ↩

-

Cheng, supra note 46. ↩

-

From the agency’s perspective, an agile backlog is simply a wish list of features in priority of business value, wherein the agency lists the functionality it desires from a system and when that can be expected. From the contractor’s perspective, the backlog is a todo list, in order of priority, listing the project deliverables and their deadlines. ↩

-

For a more detailed explanation, see Fowler, supra note 20. ↩

-

Poppendieck, supra note 32, at 9. ↩

-

See Lee & Xia, supra note 11, at 89. ↩

-

Federal Executive Round Table, supra note 56. ↩

-

Lee & Xia, supra note 11, at 90. ↩

-

ID. at 89, 92. ↩

-

ID. at 89. ↩

-

Cao & Ramesh, supra note 28, at 63. ↩

-

ID. at 64. ↩

-

See Fowler, supra note 20. ↩

-

Federal Executive Round Table, supra note 56. ↩

-

Cao & Ramesh, supra note 28, at 60. ↩

-

See ID. at 63. ↩

-

Poppendieck, supra note 32, at 3. ↩

-

See Szalvay, supra note 6, at 6. ↩

-

See Royce, supra note 19, at 4. ↩

-

DoD Acquisition Report, supra note 1, at 47–48. ↩

-

Id. ↩

-

Id. ↩

-

Royce, supra note 19, at 4. ↩

-

Szalvay, supra note 6, at 8. ↩

-

Cao & Ramesh, supra note 28, at 64. ↩

-

Id. ↩

-

ID.; DoD Acquisition Report, supra note 1, at 53. ↩

-

Cao & Ramesh, supra note 28, at 65. ↩

-

DoD Acquisition Report, supra note 1, at 47–48. ↩

-

Cao & Ramesh, supra note 28, at 65. ↩

-

Id. ↩

-

DoD Acquisition Report, supra note 1, at 53. See Poppendieck, supra note 32, at 15. ↩

-

See Poppendieck, supra note 32, at 3. ↩

-

ID.; DoD Acquisition Report, supra note 1, at 47–48, 53. ↩

-

Chief among agile’s criticisms in the private sector may be that its emphasis on functional, rather than technical requirements often under-serves the project’s non-functional goals. Cao & Ramesh, supra note 28, at 64–65. ↩

-

Glen B. Alleman et al., Making Agile Development Work in A Government Contracting Environment, in Conference Papers, Agile Dev. Conference 114, 114 (2003). ↩

-

Cao & Ramesh, supra note 28, at 64. ↩

-

Earned value project management relies on progress payments, which are payments based on the value the contractor earned during that period rather than on the level of completion as it relates to an established project plan. Alleman et al., supra note 109, at 114. ↩

-

Cao & Ramesh, supra note 28, at 64–65. ↩

-

Id. ↩

-

Cheng, supra note 46. ↩

-

ID. Multiple, small investments of time and effort acknowledge that humans make mistakes and mitigates project risk through independent, componentized steps. FCC Interview, supra note 36. ↩

-

Early engagement between technical contacts, COs, and legal teams is crucial to a successful project. The process itself should be agile. The requirements writing process should not be waterfall if the project is not. FCC Interview, supra note 36. ↩

-

Cheng, supra note 46. ↩

-

Sherman, supra note 15, at 3. ↩

-

Cheng, supra note 46. ↩

-

Fowler, supra note 20. ↩

-

Cheng, supra note 46 (commenting “an entrenched project management culture has yet to give up rigid parameters, documentation and processes”). See Hilary Berger, Agile Development in a Bureaucratic Arena, 27 Int’l J. of Info. Mgmt. 386, 392 (2007) (noting “where the organizational nature is one of bureaucracy and hierarchical status,” a culture “counter-productive to agile development” emerges because “management driven responsibility inhibits the fast, authoritative decision-making activities” that are “crucial” to agile). ↩

-

See Jerry Mechling & Victoria Sweeney, Overcoming Budget Barriers: Funding IT Projects in The Public Sector 14 (1997). ↩

-

See ID. at 8. ↩

-

See ID. ↩

-

ID. at 11. ↩

-

See ID. ↩

-

Cheng, supra note 46. ↩

-

Sherman, supra note 15, at 230. ↩

-

See ID.; Emmett E. Hearn, Federal Acquisition and Contract Management 55 (5th ed. 2002). ↩

-

Sherman, supra note 15, at 251. ↩

-

See FAR Part 15. ↩

-

Sherman, supra note 15, at 299–301. ↩

-

ID. at 301. ↩

-

ID. at 302. ↩

-

Id. ↩

-

H.R. Rep. No. 92–1188, at 1, 2 (1972). ↩

-

FAR 36.6. ↩

-

Id. ↩

-

FAR 36.602–1(a). ↩

-

40 U.S.C. § 1103(d) (2006). ↩

-

FAR 36.601 specifically notes that “services that do not require performance by a registered or licensed architect or engineer . . . should be acquired pursuant to parts 13, 14, and 15.” ↩

-

National Defense Authorization Act of 1996, Pub. L. No. 104–106, 110 Stat. 659, 689 (1996) (codified in scattered sections of 40 U.S.C. and 41 U.S.C.). For a comprehensive overview of the ITMRA (later known as the Clinger-Cohen Act) reforms, see Stephen W. Feldman, Clinger-Cohen Act of 1996; GAO Procurement Protest Authority, 1 Government Contract Awards: Negotiation and Sealed Bidding § 1:12 (2010). ↩

-

FAR 39.103. ↩

-

Cohen Plans IT Procurement Reform Legislation, 37 Gov’t Contractor ¶ 83, Jan. 15, 1995, at 8–9 (observing that the act’s sponsor argued that “by the time a contract is awarded, the technology that is being bought is obsolete”). ↩

-

Modular Contracting White Paper, supra note 41, at 24 (identifying a module as an “economically and programmatically separable segment” that “should have a substantial programmatic use even if no additional segments are acquired [and as]… a functional system or solution that is not dependent on any subsequent module to perform its significant functions”). ↩

-

FAR 39.103(a). ↩

-

ID.; FAR 2.101. A “major system” is a system estimated to exceed million or the threshold defined by OMB Circular A-109 or that is designated a “major system” by the head of the agency responsible for that system. FAR 2.101. ↩

-

FAR 39.103(b). See Danielle Conway-Jones, Research and Development Deliverables under Government Contracts, Grants, Cooperative Agreements and CRADAs: University Roles, Government Responsibilities and Contractor Rights, 9 Computer L. Rev. & Tech. J. 181, 192 n.75 (2004). ↩

-

FAR 39.103. ↩

-

Strengthening IT program management by exposing best practices and aligning IT procurement with innovation is a central tenet of the White House’s plan to reform federal IT. Kundra, supra note 13, at 17 (noting “the acquisition process can require program managers to specify the Government’s requirements up front, which can be years in advance of program initiation . . . We need to make real change happen . . . by educating the entire team managing IT projects about the tools available to streamline the acquisition process.”). ↩

-

Ideally instructors would create a scalable model outlining the various issues contracting agencies must broach before pursuing an agile project, such as how to ensure robust competition, how broad or specific the statements of work should be, whether to award to a single vendor or multiple vendors, and when to use fixed-price contracts or rely instead on other contracting vehicles. See generally Kundra, supra note 13. ↩

-

An example of a functional approach would involve requiring that a system use industry best security practices rather than describing a particular encryption algorithm. ↩

-

This holds true for both the FAR and DoD regulations. DoD Acquisition Report, supra note 1, at 4. ↩

-

FAR 36.601. ↩

-

FAR 36.602–1. ↩

-

FAR 36.601(4)(a)(3). The U.S. Bureau of Labor and Statistics classifies the software engineering role as a subset of computer specialist, while all other engineering disciplines are a subset of engineer. Additionally, software engineers do not receive professional engineering licenses from the state. If a state were to grant such a license, this would serve as an interesting test case. ↩

-

FAR 39.103 (implementing the Clinger-Cohen Act of 1996, Pub. L. No. 104–106). ↩

Ben Balter is the Director of Hubber Enablement within the Office of the COO at GitHub, the world’s largest software development platform, ensuring all Hubbers can do their best (remote) work. Previously, he served as the Director of Technical Business Operations, and as Chief of Staff for Security, he managed the office of the Chief Security Officer, improving overall business effectiveness of the Security organization through portfolio management, strategy, planning, culture, and values. As a Staff Technical Program manager for Enterprise and Compliance, Ben managed GitHub’s on-premises and SaaS enterprise offerings, and as the Senior Product Manager overseeing the platform’s Trust and Safety efforts, Ben shipped more than 500 features in support of community management, privacy, compliance, content moderation, product security, platform health, and open source workflows to ensure the GitHub community and platform remained safe, secure, and welcoming for all software developers. Before joining GitHub’s Product team, Ben served as GitHub’s Government Evangelist, leading the efforts to encourage more than 2,000 government organizations across 75 countries to adopt open source philosophies for code, data, and policy development. More about the author →

This page is open source. Please help improve it.

Edit